Memory is a layered thing built from accretions of time. I was reminded of this on a recent conference trip to Seattle, a place I had long wanted to visit. A writer friend who knew the city educated me about it over dinner one evening during my stay. What we saw rising around us on steeply angled hills had been a build-over. An older Seattle she encouraged me to see existed, invisible as a ghost, beneath our feet.

There had been a fire, she said, the Great Fire of 1889 . In its aftermath city officials had decided to rebuild, but not before raising the city floor between twelve and twenty-four feet depending on location. The fire had been a blessing in disguise, one that allowed engineers to tackle a more entrenched problem: periodic flooding from Elliott Bay. While a new city emerged, an old one was transformed into a shady underground warren almost immediately colonized by opium parlors, pre-Prohibition bars and homeless people seeking refuge from the wet, the cold and the gray.

Seattle, it seemed, sat on den of memories, an urban unconscious. In the days that followed my dinner, I would remember what my friend told me as I processed my experiences, some of which astonished me for their strangeness. I did not know Seattle; nothing and no one tied me to it in any way. Yet from the day I arrived, memories rose up from the depths of my mind and washed over me like ocean tides.

It began with the appearance of a girl at the budget digs I’d found off Pike’s Place and First Avenue. Climbing up entrance stairs that inclined at a knee-cracking forty-five degrees, suitcases in tow, a shadow flickered on the edge of my vision. I paused and looked up. A girl tripped past me, carrying no baggage at all, her long brown hair hanging loosely around her shoulders. The wire-framed glasses perched on her nose caught the light and glittered. Welcome to your past, the wry smile on her face seemed to say. Enjoy it.

The girl was me; and—so I thought—a product of travel fatigue and disorientation. Years before, during the restlessness of early adulthood that took me on two railway tours of Western Europe, I had been the girl with long brown hair, one young hosteler among many. Now, her older counterpart had taken to the hosteling scene again, a middle-aged outlier among the twenty and thirty-somethings around her. Practicality had dictated lodging choice. But that choice had also catapulted that older woman back in time.

I checked in and climbed another flight of stairs to the room where I would be sharing with five strangers. Small and stuffy with padlocked locked cubbies instead of closets, sheets that slid off plastic-covered mattresses and curtained beds that felt like train couchettes, the room smelled of closeness and human contact. There was no curfew; people seeped in from clubs and pubs at all hours of the night and shambled up bunk bed ladders, regardless of whether you were trying to sleep or not. It felt like college.

If the first day jarred with its strangeness, the second day shocked through its sense of utter normality. Though I was a tourist in a new city as much as I was also one in a space of youth. Sprawling on my bed between panel sessions and book fair crawls, I listened to the street musician under my window picking chords on an electric guitar and thought of street musicians who played for passers-by in my old college town. Chatting with my young suite mates—most of whom were also MFA student conference goers—I realized that once upon a time, they could have been the young people I used to teach. As physically uncomfortable as my accommodations were, they also spoke to a part of me that recognized them as iterations of my own history.

As I mused on my experiences, I realized that the interplay of past and present infused almost everything. The old friends I had come to see at this conference had come from different phases in my life: the mentor who knew me when all I had were fragmented narratives and more words than I knew what to do with; the poet who knew me when we were both struggling to towards new professional identities in the aftermath of academia. Even the setting, though new, called to mind a time and place when I lived by the sea. The ocean was itself a memory, one that contained everything and everyone I had ever known growing up in California.

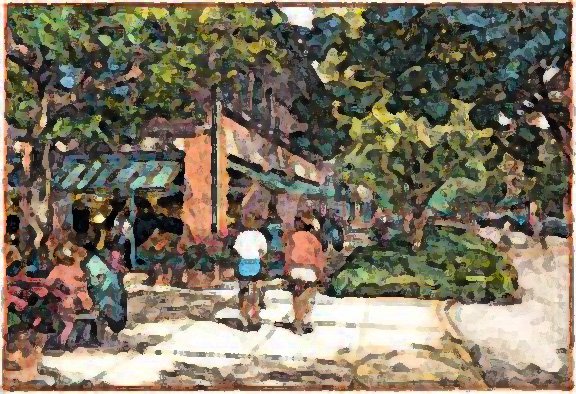

By the third day of my visit, I could feel the flood of it all overwhelm me. I loved the city, loved being around people who loved words and craft as much as I did. But I needed time away from the things and people I had invited into my life. To reflect. Digest. Incorporate. And so it I ventured east of the city to sit alone in the green of Viretta Park—this time, deliberately so—with more recollections of youth. Nirvana front man Kurt Cobain’s memorial bench was there; and I wanted to be there, too, filling my lungs with frigid air and remembering music that had actually spoken to me.

The park surprised me with its stillness, its smallness. I took out the candle I’d brought with me, lit it and slowly circled the bench, humming bars from “Come as You Are.” And I remembered the girl with long brown hair. Once she had followed arrows spray painted on tombs in the Père Lachaise Cemetery to Jim Morrison’s grave in Paris. She listened to his music on the radio and like it well enough. But the visit was all surface gesture, a morbidly romantic way to celebrate a rebel musician from a generation she could only admire from a distance.

Now the girl had become me, the older woman who moved with purpose. Everything, right down to candle in her hand, had been planned. Once I had worshipped Nirvana’s Nevermind album by lying on the floor of my apartment, the better to feel the crash and scream of guitars shiver my spine. Three years after that, Cobain overdosed one month before he took a shotgun to his head and died. I was just 28; still innocent, but on the verge of real adulthood. In the decades that followed, I saw things, did things, felt things—very dark things—the girl with long brown hair could never have imagined. But unlike the musician whose life I had come to celebrate, I survived mostly intact, but never quite the same.

Sitting in that park afterward, alone save for the occasional passing car or jogger, it came to me that nothing could ever be a blank slate for anyone who lived long enough. Everything had history; but the older I got, the more things followed rules of cause and effect I could not always see or understand. I was in Seattle because of a conference, because of friends, because I loved of words. And while there, was making new memories to coexist simultaneously with old ones Just the way the invisible underground labyrinths my friend had described co-existed with beauty my eyes could see and the wonder my heart could feel.