The living room window is the best place in my house to watch the emergence of Austin’s month-early spring. Taller than it is wide, that window overlooks a tiny garden gone wild with exuberant heads of broccoli, kale and lettuce. But on a recent Saturday, I noticed the fine patina of dust that clung to the outside panes. It had been there for a while; but something about the way the morning sunlight struck the window made that grime look more blatant. And made me realize with some consternation that I could not remember the last time I had given those widows a good cleaning.

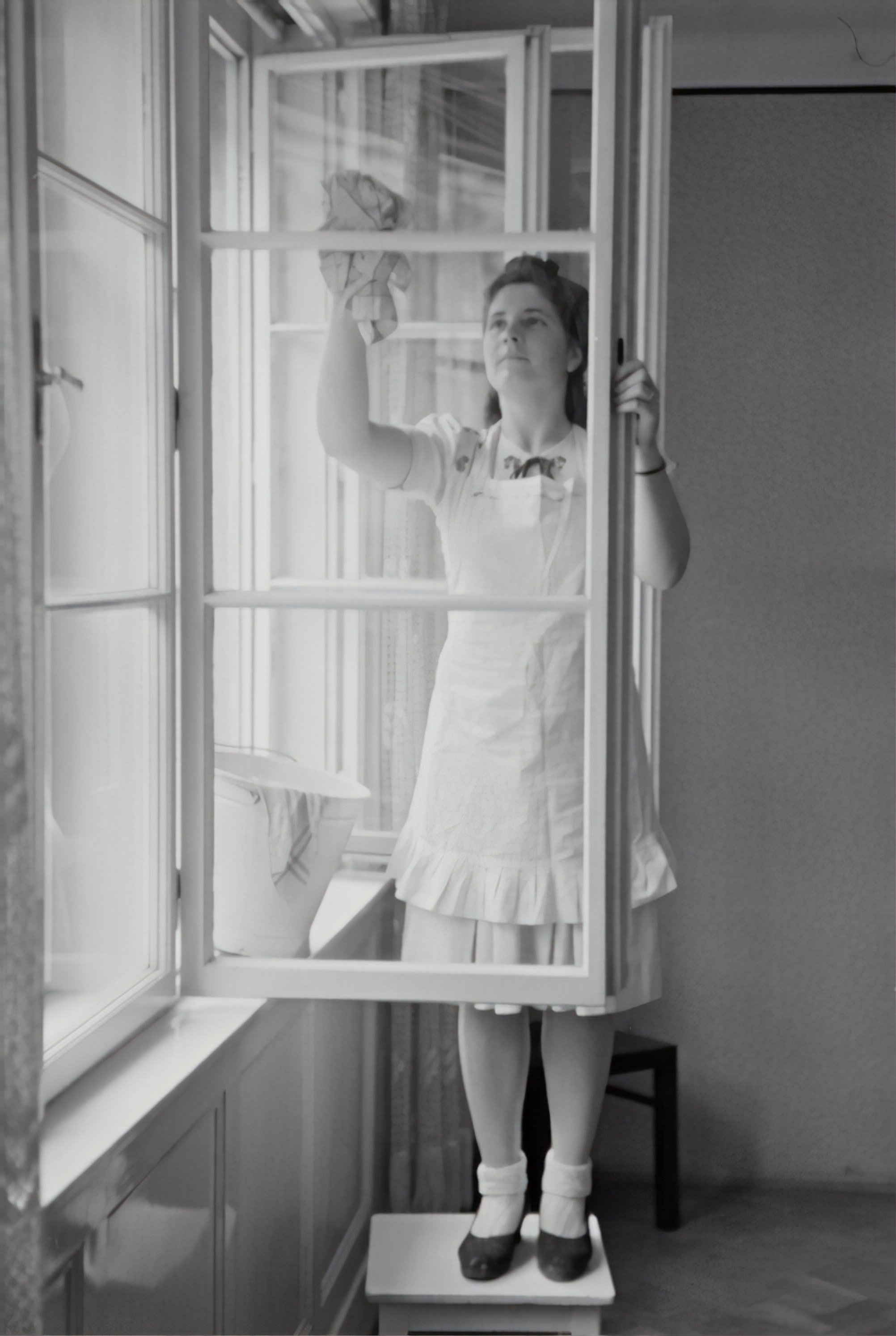

I wasn’t in the mood to interrupt my morning tea, but that dirt irritated me. Grumbling, I rolled up my sleeves and Windexed the inside window panes. Grumbling some more, I went outside, scrubbed down the outside panes with soap and water, hosed them down, then rubbed then dry. My tea was getting cold so I went back into my house to finish it. The grumbling stopped dead when I saw how much the light had brightened. Then vanished entirely when I saw the view from my newly cleaned windows. The cheerful tangle of garden sprouts, the sidewalk and street just beyond it, the blue-green house facing mine—all of it shined with the clarity and freshness of a newborn miracle.

Cleaning windows had washed away the bother and dismay. As I finished my tea, though, I couldn’t help wondering why I’d even felt those things to begin with. When I lived in apartments it didn’t matter that windows went unwashed and that closets were left to gather dusty cobwebs. And that countertops, stoves, refrigerators and bathrooms saw only light, infrequent cleanings with a purple liquid that smelled incongruously of pine and roses.

Catch-as-catch-can was good enough. That is, of course, until the carpenter ants invaded and the bedbugs bit, which happened when summer heat combined with the carbon dioxide of human exhalations turned insects mean. But I was a migratory animal, the wild thing who absolutely could not be bothered with anything that smacked of too much domesticity. Besides which, if the space wasn’t mine, why bother? Why make the investment of time and energy?

I can’t say I feel the same anymore. Not because I particularly care what neighbors think of me or my dirty windows. Or because some innate housewifing instinct that not even the most scrupulous avoidance of matrimony could suppress has finally surfaced. But because things like home space matter to me now that I’ve opted for a more settled life. And because, having lived on the edge for too many decades, I can appreciate how much that space, fragile as glass, is really worth. Wiping away the dirt that inevitably collects honors both the space and the struggle that made it mine.

There’s something, too, that I enjoy about the pleasure of clean. No matter how much I detest routine chores, I know that my grime-wrangling will yield a temporary—but no less coveted—peace. The only down side is that the cycle will begin immediately after the last clean-up, when the cat spills food onto the floor and the shoes I clean off at the entrance still bring dirt into the house. But the effort and fight are worth it. In an increasingly messy world, small things like cleaning windows feels like a radical act of self-preservation. A way of staving off the shadows and chaos that press against the edges of the well-ordered little community where I live.

I doubt that any of this would have made sense to me before and especially not during the restless years of youth and early midlife. Age, it seems, has brought redefinition of pleasure and what constitutes reward. The hyper-mobility and an excess of freedom I craved no longer suit the person I’ve become. I was reminded of this when I stumbled across the manic Facebook reel musings of another fifty-something who wondered how in hell he’d gone from adrenaline junkie addicted to constant change to the homeowner who loved watching wild birds peck at the grain feeder in his yard.

Like my fellow Gen-X gray-hair, I would never have guessed that doing things I hated like cleaning my house would bring contentment. Or that the ordinariness of my life—which in global terms, is exceptional for its relative stability, safety and abundance—would give me satisfaction. It’s like the view from new-cleaned window panes: you look and look and do not find until you realize it’s right in front of you.